D-Day at Oflag 64

[This essay was written in 2019]

This June 6th marks the 75th Anniversary of the D-Day landings at Normandy. On that same day, far from the Atlantic coast, in a town in northeast Poland, a group of American prisoners-of-war executed their own subversive attack on the Third Reich. Their weapons included the secret radio that the POWs hid in their barracks attic, the resourceful creations of the POW Entertainment Committee, and the POWs’ daily newssheet, written and published by a few determined American prisoners. The news staff included a former Washington Post reporter, a Pulitzer Prize-winning AP war correspondent, and a future CIA operative--my father, 2nd Lieutenant Seymour R. Bolten.

My dad told us only a few short stories from the war. Long after he passed away, however, I discovered his drab-green footlocker buried in a corner of the garage. It contained journals, photos, an escape map, and hundreds of letters and documents from his POW life. In one of his earliest letters--to his Glee Club director at New York University—he wrote of the days-long battle in February 1943 in Tunisia in which he was captured, “I really thought I’d be singing in that heavenly choir.”

On June 6, 1943—four months after his capture and one year before D-Day—the first 35 POWs arrived at Oflag 64 in Szubin, Poland, the only POW camp the Germans established for the officers of the American ground forces. My dad, age twenty-one arrived a few days later. Like the others, he arrived via a three-day train trip, locked in a box-car. Suffering from exhaustion and dysentery, he and others shuffled through the camp’s tall gates and past the layers of barbed wire.

My father’s POW ID card, issued to him in March 1943, before he arrived at Oflag 64.

With the help of supplies from the YMCA, and under the leadership of their Senior American Officer, Colonel Thomas D. Drake, a WWI cavalry veteran, the American POWs organized. They established a theater program and put together a Glee Club (my dad sang tenor, I learned). They fielded a softball team and founded the “Little College of Szubin.” They set up a library, a tailor shop, and a book bindery.

The Germans allowed these activities because they were following the rules of the Geneva Convention, and because they believed that busy POWs would not be escape-planning POWs. They were mistaken. The camp’s entertaining singers and energetic softball players not only kept the POWs occupied, but also diverted the guards’ attention.

The POWs’ clandestine Security & Escape Committee coordinated escape plans and tunnel digging proposals, and the sending and receiving of coded letters and clandestine packages. With cigarettes and chocolates sent in packages from home, they bribed guards for information, food, and tools. Every evening after Lights Out, they assembled “The Bird,” their secret radio. The Bird “sang” coded messages and news updates broadcast over the BBC.

Using his college German, my dad became one of the camp interpreters. He facilitated discussions between Colonel Drake and Oberst Schneider, the camp Kommandant, and between his fellow POWs and the guards. He accompanied sick POWs on hospital visits outside of the barbed wire, which afforded him opportunities to observe and exchange intelligence.

The POWs also published a daily, one-page, poster-sized newssheet, The Daily Bulletin, that reported war news. Prisoner Larry Allen, a Pulitzer-prize-winning Associated Press war correspondent was its first editor.

The staff of The Oflag 64 Daily Bulletin newssheet. My dad is front row, far right. Pulitzer Prize and AP war correspondent Larry Allen is behind him. Photo taken January 1944 by a guard.

Allen hand-lettered the broadside’s tall columns and bylined it the “Szubin Bureau of the AP.” His sources were the German-supplied newspapers and magazines published by the Nazi Propaganda Ministry, and the English and German-language radio broadcasts the guards piped in over the Oflag 64 loudspeakers. My dad translated the German. Together, he and Allen interpreted the propaganda. To protect their Bird information, my dad and Allen used coy and indirect language in their war news copy.

In his book “Americans Behind the Barbed Wire,” Lt. Frank Diggs, a reporter for The Washington Post before the war, said about my dad’s interpreting, “Seymour had an uncanny sense for appropriate news and a built-in sense of humor. He was therefore able to pick out endless faux pas put out by the serious-minded German propagandists.”

Each day, the Oflag 64 POWs lined up to read the newssheet, posted outside of their Mess Hall. One of the few things my dad told me about his POW life was that even the Germans stopped by to read The Bulletin. They knew it was their most accurate source of information.

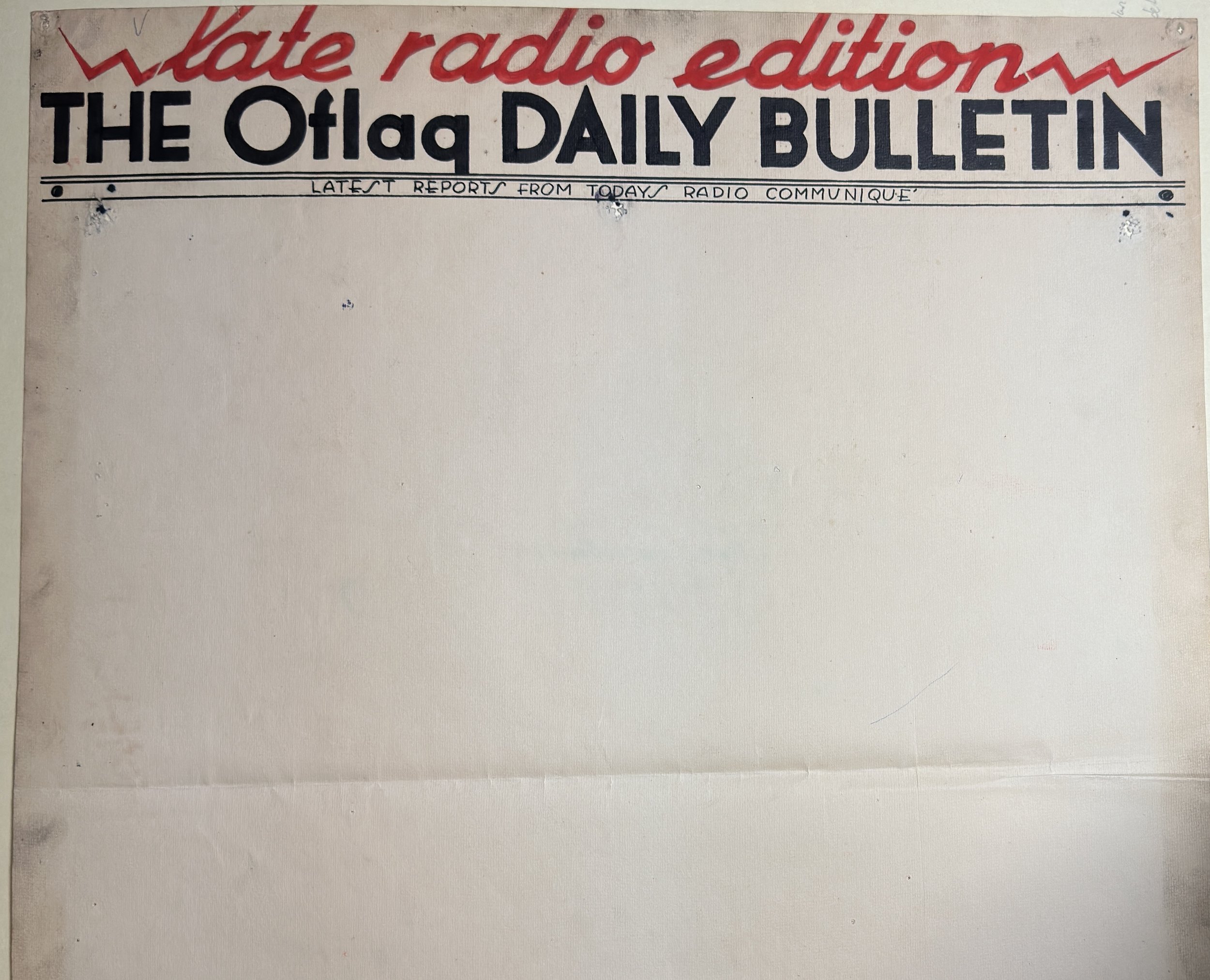

Masthead of The Daily Bulletin. Each day the POW editors pinned a new issue to it on the Mess Hall bulletin board. You can see the multiple pin holes here. U.S. Army Heritage & Education Center, Carlisle PA.

In the spring of 1944, the Germans repatriated Allen. Frank Diggs joined my dad on The Bulletin.

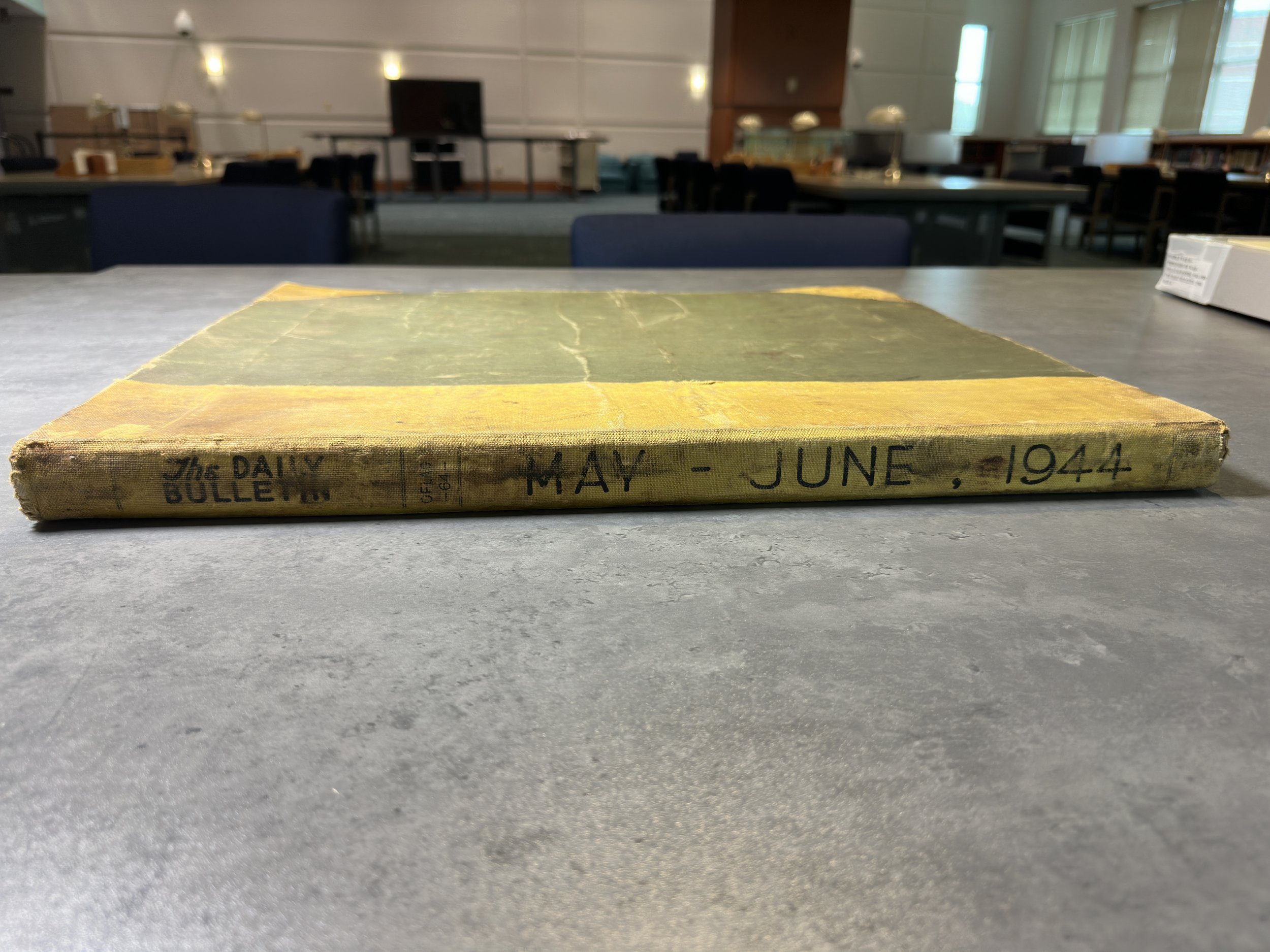

At the end of each day, Diggs passed along the Bulletins—first to the men in the infirmary, and then to the POW book bindery. The POW “book gnomes” stitched and glued the canvas-covered, drab-green volumes. Each tome held two months of newssheets, measured about three feet by two feet, and weighed about four pounds.

One of the bound volumes of The Daily Bulletin that I found at the U.S. Army Heritage & Education Center in Carlisle, PA.

Throughout the winter of 1943-1944, The Bulletin tracked the disappointing war news, while my dad and the others endured frostbite and near starvation. In the spring of 1944, to boost morale and to keep the POWs occupied, Colonel Drake asked Oberst Schneider’s permission for the men to plan a one-year anniversary party. With the Kommandant’s blessing, the POW Entertainment Committee spent the next two months planning the festivities for the Anniversary Carnival: June 6, 1944.

At the same time, The Daily Bulletin--along with the rest of the world--speculated on the much-anticipated Allied invasion of Western Europe. The men who gathered around the bulletin board read speculations like these:

Excerpt from The Oflag Daily Bulletin, May 19, 1944. “Four more completely moon-less, invasion-perfect nights remain in May.” U.S. Army Heritage & Education Center, Carlisle, PA

But, as May became June, the POWs grew discouraged. POW Captain Tony Lumpkin wrote in his Oflag 64 journal, published later as Captured Yesterday, “The morale is down. All are prepared to spend some time in this camp.”

On June 5th my dad wrote to his girlfriend:

Dearest Annette:

Tomorrow marks the anniversary of the establishment of the first All-American ground officer’s camp under our host’s sponsorship one year ago. In true American fashion it will be celebrated with games, entertainment, and the best food we can muster together.

Our orchestra is pretty good…its theme song is “Time on my Hands…”

On the morning of June 6th, 1944, The Daily Bulletin ignored the war and announced, “American Garrison Marks First Women-less Anniversary Behind Schubin Barbed Wire.”

The morning issue of The Oflag Daily Bulletin, June 6, 1944. “The Anniversary Program…is combat-loaded with games, music, awards…But no women—in keeping with [a] now year-long tradition.” U.S. Army Heritage & Education Center, Carlisle, PA

Immediately following morning Appelle--one of several times per day when the guards counted the prisoners--the Entertainment Committee’s Carnival Midway team got to work.

Col. Drake opened the Midway over the camp loudspeaker. Around the camp, men stopped in place to listen to their Colonel.

June 6, 1944 marks the first anniversary of Oflag 64. The past year has been filled with ceaseless effort to improve conditions inside the barb wire so that the mental and physical life of all might be maintained and improved…[W]e now have a camp and community life, contributed by each and everyone…

…Let no man believe that there is a stigma attached to having been honorably taken captive in battle. Only the fighting man ever gets close enough to the enemy for that to happen...

Be proud that you carried yourselves as men in battle and in adversity…

A brief silence inside the wire erupted into cheers.

On the Midway, barkers enticed the carnival goers to try the games. Knock over a milk bottle, and win a hunk of German cheese (the men agreed that no one was allowed to eat this stinky cheese inside the barraks), or the most popular—the Lieutenant Colonel Dunk Tank. The lieutenant colonels, including John Waters, son-in-law of General George S. Patton, were good sports and got soaked for the cause. The German guards, peppered around the perimeter of the barbed wire, kept light watch and tried not to smile at the American celebration.

Fortune tellers wearing turbans could predict your fate, and the POWs from Hawaii wore grass skirts and danced the hula. Around 11am, the officer who had been secretly monitoring the Bird sidled up to Colonel Drake and spoke to him in a hushed tone. The whispered message galloped through the carnival crowd, “the invasion is on.”

The POWs could not let on they knew until the Germans did. They stifled their joy, but played their games at an increased pitch.

Around 1pm, German radio announced over the loudspeakers that the invasion “attempt” had begun. The POWs let loose their pent-up cheers. The smiles faded from the Germans’ faces. The guards stood taller and held their weapons tighter. The Nazi Security Officer, Hauptman (Captain) Zimmerman, doubled the number of guards on duty.

My dad and the rest of The Bulletin staffers rushed back to their news-bunkroom to write up a “Newsflash” issue. Zimmerman stood over them. He wanted to know how much the Americans really knew about the invasion, and when they knew it. Captain Doyle Yardley wrote in his POW journal that day, later published as Home Was Never Like This, “Sometimes it’s more advantageous to let people believe what they want to think, especially in times of war.”

The Daily Bulletin on the afternoon of June 6, 1944. U.S. Army Heritage & Education Center.

Back on the Midway, the POWs’ enthusiasm kicked into unbridled high gear. They dug into the Red Cross food tins they had been saving for the party, and the betting POWs revised their end-of-the-war estimates.

In New York City that day, my great aunt wrote to my father:

June 6, 1944

Dear Seymour-

I just spoke to your mother over the phone...To-day we are all listening to the radio for important news from overseas and we are wondering if you know anything that is going on…

Love, Aunt Betty

Back at camp, after a festive dinner of fried Prem (canned meat, like Spam), mashed potatoes, garden carrots, and apple pudding, The Bulletin staffers pinned up the “Late Radio Edition.”

Late afternoon edition of The Oflag Daily Bulletin, June 6, 1944. U.S. Army Heritage & Education Center.

The camp loudspeakers blasted the Propaganda Ministry’s announcement that the greatest share of the Allied airborne troops had been “annihilated.”

At 7:30pm, POW band leader Bob Rankin and his Swing Band opened the evening Variety Show with “You Made Me Love You,” followed by sixteen favorites tunes sung by the Oflag 64 Glee Club. Lt. Lou Otterbein, the most resourceful prop man in theater, had been working all afternoon on a surprise finale. At the end of the show, all the performers came out on stage, each holding a piece of a banner that when combined read, “Let’s Go Ike.” As the crowd cheered, a cardboard V-1 rocket breezed down a wire strung over the top of the stage, trailing another “Let’s Go Ike” banner. The audience went wild.

The Oflag 64 Swing Band, 1943-1945. Instruments donated by the YMCA. The POWs crafted the bowties from the cardboard of their Red Cross parcels. Polish-American Foundation for the Commemoration of POW Camps in Szubin

The POWs celebrated until 10pm, well past Light’s Out. Finally, the Germans ordered an end to the day.

The following week, my dad wrote to his parents and youngest brother, Jerry:

June 15, 1944

Oflag 64

Dear Folks,

Last week on June 6 we celebrated the first anniversary of the beginning of the only all-American ground officer’s camp. It turned out to be the reason for an even bigger celebration than we figured on…

For the next seven months, The Daily Bulletin tracked the changing Western and Eastern Fronts, and the slow advancement of U.S. ally, the Soviet Red Army, rumbling toward Szubin, on its way to Berlin. One of the last surviving issues of The Bulletin was published on January 12, 1945, headlined, “Germans See Moral Victory.”

The fleeing Germans would force march most of the POWs to Germany. My dad and a few hundred others would leave Szubin courtesy of the “liberating” Soviets. During this months-long odyssey the Soviets held my dad and the others for several weeks at a refugee camp worse than any of the POW camps they had experienced, then transported them via box car to Odesa.

Throughout, my dad lugged The Daily Bulletin books. Thieves stole two of the giant tomes, and someone ripped a big chunk out of half of the pages of another. By the 1950s, Diggs and my father both lived in Washington, DC. My dad was working for the CIA and Diggs an editor at U.S News & World Report. Diggs stored The Daily Bulletin volumes in his attic. Sometime in the 1970s, the two friends drove to Carlisle, Pennsylvania and donated them to the U.S. Army Heritage and Education Center. They have left us a unique interpretation of the war and chronicle of their POW experience and gile. If you go to the archive, and turn the books’ tall and stiff pages, you’ll see my dad’s loopy handwriting on the backs of many of them.

My dad passed away on June 6, 1985, exactly forty-one years after the Oflag 64 Anniversary Carnival. He was buried at Arlington National Cemetery, in an elegant military observance that included a horse-drawn caisson, a twenty-one gun salute, and taps. “Your father would have loved this,” my mother whispered to me. Not because of the honor to him, but because of the patriotic ceremony. I think he would have also liked that The Daily Bulletin is still reporting.

My father and Larry Allen, reunited in the late fall 1945 in Berlin. Allen was en route to his AP assignment in Warsaw. My dad was serving with the Office of Military Government for Germany.